Ethelene Rachel Thomas Reed: The Woman Behind the Reed Legacy

Before the name Reed became associated with automobiles, innovation, and customer service in Rockville, Maryland, there was a young farm girl growing up in rural Frederick County. Ethelene Rachel Thomas, born September 16, 1894, spent her childhood on her family’s farm on Butterfly Lane in Buckeystown, Maryland; a quiet countryside that helped shape the woman who would later stand beside Lewis Reed, founder of Reed Brothers Dodge.

Ethelene was the daughter of Clinton Clay Thomas (1856–1940) and Mary Elizabeth Thomas, lifelong farmers whose roots ran deep in Frederick County soil. Their farm, located along Butterfly Lane, was part of a long-established agricultural corridor of small family homesteads, fields, and barns that fed nearby towns for generations.

Growing Up on the Thomas Family Farm

Life on the Thomas farm followed the steady rhythms of the seasons. Long days were filled with planting, harvesting, tending animals, and preserving food for winter. Like many rural children at the turn of the 20th century, Ethelene learned responsibility early, helping with household work and farm chores while growing up in a close-knit, hardworking family.

Butterfly Lane, once little more than a farm road, connected families like the Thomases to Buckeystown and the larger Frederick County community. Though modest, the farm represented stability, perseverance, and a deep connection to the land; values that Ethelene carried with her throughout her life.

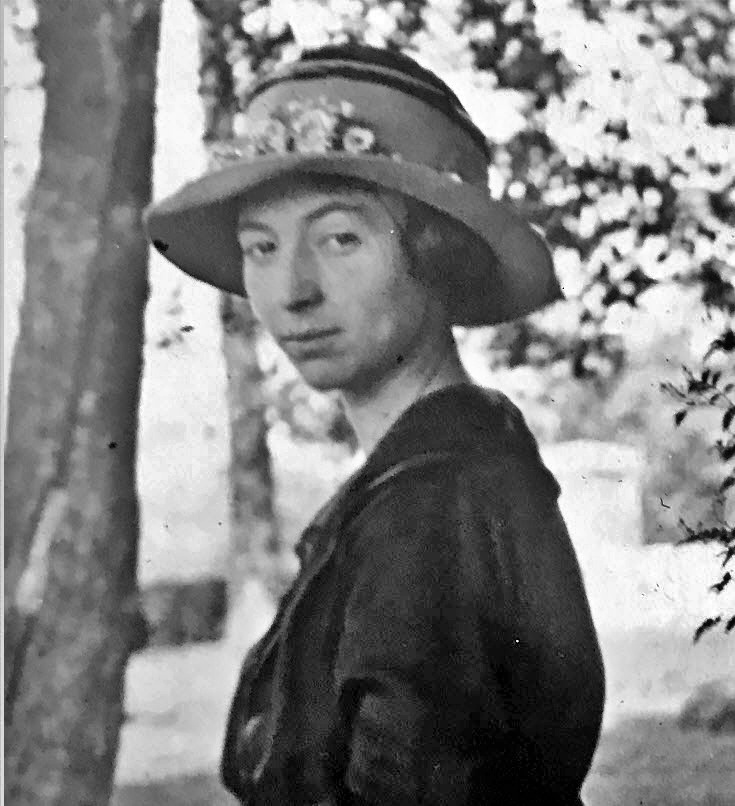

Ethelene Reed was the matriarch of a family that became synonymous with the automotive industry in Maryland. In this photo, her poise and fashionable attire reflect the burgeoning middle-class elegance of the early 1920s.

From Farm to Classroom

Before her marriage to Lewis Reed, Ethelene was a teacher in the Maryland public school system; a role that reflected her commitment to service, learning, and community. Teaching offered young women of her generation one of the few professional paths available, and Ethelene embraced it with the same dedication she had learned on the family farm.

A New Chapter in Rockville

Ethelene Rachel Thomas seen in the passenger seat, joined by her sister, Celeste Thomas, with their father, Clinton Clay Thomas, in the back. Photographed by Lewis Reed, circa 1918.

As the country changed, so did Ethelene’s life. She eventually left the farmland of Frederick County and married Lewis Reed, a gifted photographer and entrepreneur who would go on to found Reed Brothers Dodge in Rockville. While Lewis built a business that helped introduce the automobile age to Montgomery County, Ethelene became an essential partner in that journey.

Ethelene Rachel Thomas and her sister, Celeste Thomas Brown, in a 1918 Oldsmobile Club Roadster. Photo taken by Lewis Reed at the Clinton Clay Thomas family farm, located on Butterfly Lane in Buckeystown, Maryland, circa 1918.

Not a great deal has been published about Lewis Reed’s wife, Ethelene Rachel Thomas, despite her central role in the family and in this story. This post is offered as a tribute to her life, her quiet strength, and the rural values she carried from Butterfly Lane into the heart of the Reed legacy.

Ethelene Rachel Thomas Reed was also my maternal grandmother, making this story deeply personal. Preserving and sharing her history is part of honoring not only her life, but the generations that followed and the legacy she helped create.

Ethelene Rachel Thomas Reed passed away on March 15, 1977, but her life remains an important link between the rural roots of Maryland and the modern legacy of Reed Brothers Dodge. From the fields of Butterfly Lane to the streets of Rockville, her story reminds us that our dealership’s history is not only about cars; it’s about people, family, and the values passed from one generation to the next.

“The Boardwalk” Along the Waterfront at Chesapeake Beach, Maryland, Early 1900s

In the early 1900s, the Chesapeake Beach Railway Company offered Washingtonians more than transportation, it promised escape. At the rail line’s eastern terminus, a bustling boardwalk emerged along the Chesapeake Bay, carefully designed to attract crowds with hotels, amusements, and sweeping waterfront views. This was a new kind of destination, where leisure was planned, marketed, and delivered by rail.

Lewis Reed recognized the historical significance of this scene and turned his camera toward it. His photographs of the Chesapeake Beach boardwalk capture the rhythms of a day spent seaside: visitors strolling between attractions, pausing to take in the view, or gathering near the latest amusements. Among the highlights of his images is the Griffith Patent Scenic Railway, an early roller coaster whose curves and speed symbolized the era’s fascination with innovation and thrill. (click on thumbnails to view gallery)

Reed’s photographs preserve more than a popular resort, they document a moment when railroads shaped recreation and when leisure itself became part of the modern experience. Through his lens, the Chesapeake Beach boardwalk is frozen in time, offering a vivid glimpse into how Americans relaxed, traveled, and found excitement at the dawn of the 20th century.

Then and Now: Hotel Cape May, 1919

People have been visiting Cape May, “the nation’s oldest seashore resort,” for longer than America has been a country. That makes Cape May the perfect place to look back on over 100 years ago and from today — then and now.

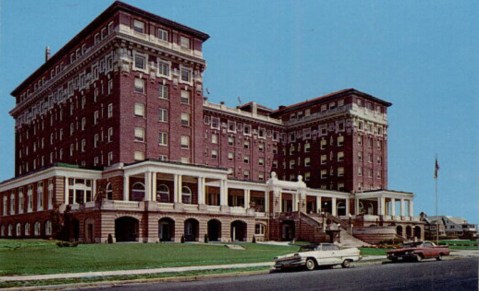

A bit of Hotel Cape May history: The Christian Admiral, formerly Admiral Hotel and Hotel Cape May, was a luxury beachfront hotel located in Cape May, New Jersey. Opened in 1908, as the Hotel Cape May, the ornate hotel was abandoned five years later due to bankruptcy. It was then sold at a Sheriff’s sale. The hotel was leased by the War Department as a hospital from 1918-1919 during WWI. Afterwards, it was again abandoned. In 1932, the Admiral Hotel company purchased it and renamed it the Admiral Hotel. They too went bankrupt in 1940. The military returned for WWII from 1941 to 1945 and afterwards it was once more sold at Sheriff’s sale. It opened and closed multiple times before being abandoned again in the 1950s. Reverend McIntire saved it from demolition in 1963, and operated it until his organization too, went bankrupt. The Christian Admiral never made a profit for any of its owners and was the cause of six bankruptcies. Nonetheless, it was a gorgeous hotel and one of the most recognizable and beloved buildings in Cape May. The people who liquidated McIntire’s organization shopped the hotel around, but it was deemed too far gone to save. Engineer estimates were $20 million and above, just to make it structurally sound and from $60-$80 million to restore it. The hotel was razed in 1996.

Hotel Cape May (THEN): The Christian Admiral Hotel, originally known as the Hotel Cape May, was erected in the Beaux-Arts style between 1905 and 1908. When opened on April 11, 1908, it was the world’s largest hotel. Completed behind schedule and over budget, Hotel Cape May was part of a development project intended to bring wealthy visitors to the city and rival East Coast resorts such as Newport, Rhode Island. During its existence it would undergo five bankruptcies and ownership changes.

Edgar was a partner with his brother Lewis Reed, in Reed Brothers Dodge. During WWI, Edgar served as a Sergeant in the U.S. Army Medical Corps from February 1918 to August 1919 and had been posted to GENERAL HOSPITAL NO. 11 in CAPE MAY, NEW JERSEY. The spirit of patriotic service which swept the country prompted many persons to offer their properties to the War Department for hospital purposes. These offers included buildings of every conceivable kind, such as department stores, private establishments, hospitals, and properties in large cities. It was found that many of these could be obtained and converted into hospitals much more expeditiously than barrack hospitals could be constructed, and at less cost.

The Surgeon General recommended that the War Department authorize the leasing of the Hotel Cape May for use as a general hospital on December 18, 1917. The Hotel Cape May was located on the Ocean Drive, at the eastern end of the city, and within 100 feet of the beach of the Atlantic Ocean. Opened first as GENERAL HOSPITAL NO. 16, the designation was changed to GENERAL HOSPITAL NO. 11, March 14, 1918. The enlisted personnel were quartered in tents which were located to the rear of the building.

The Christian Admiral Hotel (NOW): In 1991, the hotel was closed by Cape May City officials. The hotel was demolished in 1996 and the site was reused for a development of single family homes. The demolition of the hotel placed the city’s National Historic Landmark status at risk.

Off-Season at the Montgomery County Fairgrounds, 1910

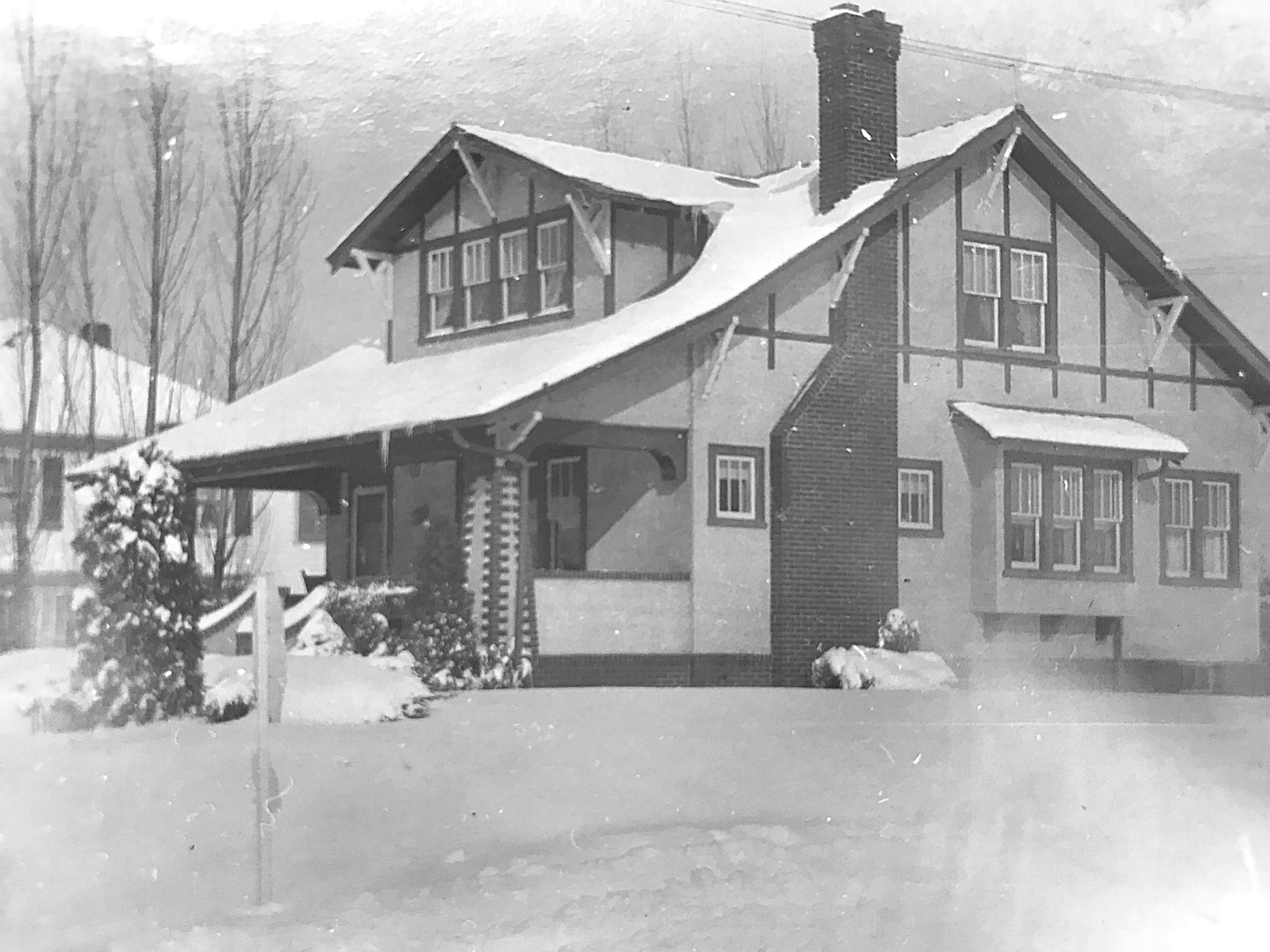

These winter photographs, taken around 1910 by Lewis Reed, offer a rare glimpse of the Montgomery County Fairgrounds during its off-season; long before crowds, exhibitions, and midway sounds returned each year. Covered in snow and largely still, the fairgrounds appear almost contemplative, preserving a moment in time that contrasts sharply with the bustle normally associated with the annual fair.

The Montgomery County Fair was held in Rockville from 1846 until 1932, serving as one of the county’s most important agricultural and social gatherings. Farmers, merchants, families, and visitors from across the region—including Washington, D.C.—came together to celebrate livestock, crops, craftsmanship, and community. Yet photographs of the fairgrounds outside the fair season are uncommon, making these images particularly significant.

Lewis Reed’s photographs show the grounds at rest. Snow blankets the open spaces, softening the outlines of fences and walkways. Buildings stand closed for the winter, including the Poultry House, which would have been a hive of activity during fair time. In these images, the structures themselves take center stage, revealing their form and placement without the distraction of crowds.

Snow blankets the fairgrounds in this early 20th-century photograph by Lewis Reed. Images such as this offer a rare view of the fairgrounds outside the fair season, documenting the site as it appeared in everyday use.

Reed’s work is notable not only for its subject matter, but for its documentary value. At a time when photography was still a deliberate and technical process, his images captured everyday scenes that might otherwise have gone unrecorded. Today, they provide visual evidence of how the fairgrounds looked and functioned in the early twentieth century, as well as a reminder of the role photography played in preserving local history.

The Poultry House at the Montgomery County Fairgrounds, photographed by Lewis Reed during the winter of 1910. Closed for the season, the building would later host livestock exhibits during the annual Montgomery County Fair.

Viewed more than a century later, these snowy scenes connect us to a slower pace of life and to a Montgomery County that was still largely rural. Thanks to Lewis Reed’s careful eye and willingness to document the ordinary as well as the celebrated, these winter moments at the old fairgrounds endure.

Snow, Tinsel, and Memories: A Century of Christmas at the Reed Family Home

With only a few days left until Christmas, I thought it might be fun to take a look at some photos from Lewis Reed’s collection that show us what Christmas trees used to look like 100 years ago. In those days, there was not wide-spread agreement on exactly what a tree should look like, which made for a lot of creativity. Not surprisingly, they were very different than the perfectly shaped tress we have on display today.

The trees were big back then and always fresh. They went right to the ceiling and were very wide. Early Christmas trees were generally fastened onto a flat board surrounded with fence-rails, snow villages and carpeted with cotton blankets of snow. The tree in the photo below has an abundance of tinsel, which grew in popularity to the point that, by the 1920s, it was common to nearly cover the tree in the decorative material.

So, what is tinsel (aka icicles) exactly? Originally made from strands of silver alloy, tinsel was in fact first used to decorate sculptures. It was only later that it became a Christmas tree decoration, employed to enhance the flickering of the candle flames. In the 1950s, tinsel became so popular that it was often used as a substitute for Christmas lights.

A small snow scene with what appears to be a miniature church is arranged at the foot of the Christmas tree. A popcorn garland adorns the tree. Photo by Lewis Reed

So, where did Washingtonians get their trees?

From The Evening Star, Washington, DC 23 December 1923:

Conduit Road on the long stretch between Glen Echo and Great Falls for many years has been a favorite hunting ground where hundreds and hundreds of families have customarily obtained scrub pine trees for Christmas week. Usually there is plenty of holly and some mistletoe to be found in the rugged and rolling hill lands which are the gateway to Great Falls.

In the early 1900s, Christmas trees weren’t the uniform, perfectly trimmed evergreens we see today. They were large, often reaching the ceiling, and proudly displayed their natural, sometimes misshapen forms. Families fastened them to flat boards, surrounded them with fence rails, and carpeted the ground with cotton blankets to mimic snow. Tinsel, originally made from strands of silver alloy, became a staple used to catch the flicker of candlelight and later, as a substitute for electric lights by the 1950s.

No room for a star on the top of this tree! And just look at those big Santa and Angel dolls. Other fun little details are notable, including a miniature church with picket fence is arranged at the base of the tree. Photo by Lewis Reed

There’s a fine art to decorating Christmas trees that’s been developing since over 100 years ago. People consider lights, garland, ornaments, skirt, and more. But one thing that’s hard to resist sometimes is just filling every available space with decorations. Clearly, that was the case years ago, too. What I like about these trees is that they are so randomly shaped and even misshapen. Folks back then didn’t trim them down to a more aesthetically pleasing symmetry like we do today.

The tradition of building miniature Christmas village landscapes, including houses, animals, and other hand-crafted wooden figures, began with the Pennsylvania Dutch in the late 1800s. Mass-produced cardboard houses, sold in dimestores, became popular in the mid-20th century. Today, these villages in good condition can be highly collectible.

Below are photos of Lewis Reed’s snow village set up under the Christmas tree decorated with vintage ornaments, tinsel, and lights. I don’t remember the odd-shaped Christmas trees, but I do remember having a lot of fun helping my grandfather set up the miniature landscapes with the varied figures, little houses, and trees at Christmastime each year. It seemed like a holiday village right out of a storybook.

A rustic picket fence is used to set off the village display. Dangling strands of tinsel hang below the tree. Photo by Lewis Reed

The snow villages were set up in Lewis Reed’s basement on top of a big table beneath a small Christmas tree. He made the snow scenes entirely by hand using wire-covered cardboard and balled up paper to make hills and pathways. The little houses and figurines would fit into the landscape with cotton ‘snow’ all around; and lights would be wired underneath.

Little houses, churches, fences, trees, and pathways were added to the scene. Some of the houses have charming light effects in the windows. The roofs of the houses were decorated with fake snow. Photo by Lewis Reed

These early Christmas villages were the forerunners of today’s elaborate holiday displays, most famously popularized by Department 56. What began as simple, handmade scenes beneath family Christmas trees eventually evolved into the collectible ceramic villages that fill shelves and mantels during the holidays today.

Old-fashioned lights can be seen on the tree, along with lit windows in the houses. The miniature houses usually had holes in the back or the bottom through which tiny lights were placed to provide illumination. Photo by Lewis Reed

Thanks for taking the time to visit. May your Christmas be merry, your New Year bright, and your holidays filled with everything that brings you joy. Stay safe and enjoy the season with family and friends!

Recent Comments