April 6, 1936 Gainesville Tornado Aftermath

One of the deadliest tornadoes in American history hit Gainesville, Georgia on April 6, 1936. And Lewis Reed was there to capture the aftermath. On the 88th anniversary of this epic tornado, I have posted eleven original snippets of history that Lewis Reed captured through the lens of his camera that day.

It all started as part of a storm system that hit Tupelo, Mississippi on April 5th, 1936. The Tupelo tornado, which registered as an F5 on the Fujita Scale, emerged from a complex system of storm cells and created a monster soon known as the fourth-deadliest tornado in U.S. history. It tore through houses, killed entire families and was even said to have left pine needles embedded into trunks of trees. One of the survivors of that storm in Tupelo was none other than a one-year-old Elvis Presley.

Unfortunately, the tragedy of that storm didn’t stop there. The system moved east overnight.

Take a look at some of the sobering aftermath photos of the deadliest tornado to ever hit Georgia … through the lens of Lewis Reed. As always, click the photos to get a better look.

View of part of the damage done to the Pacolet Manufacturing Company when a tornado struck the area. This textile mill had been established in 1901. New Holland was a community located just north of Gainesville. Photo by Lewis Reed

The devastating tornado continued beyond Gainesville, next striking New Holland, about two miles to the east, where it heavily damaged the massive Pacolet Mill, a major producer of textiles (as well as nearly 100 homes). The Digital Library of Georgia states that the Pacolet Mill was heavily damaged. Remarkably, no one in the mill was injured, as the workers saw the storm coming and evacuated from the upper floors, then ran to the building’s northeast end which remained intact after the tornado struck. (They knew where to take refuge as a result of an earlier tornado which struck in 1903, killing about 50 people in the mill.) After extensive repairs, Pacolet Mill resumed operation.

The overall destruction was barely able to be tallied. Department stores collapsed killing dozens of people, residential areas were devastated with nearly 750 homes destroyed and more than 250 were badly damaged. Buildings caught fire, trapping people inside. It was even reported that the winds were so high that letters from Gainesville were blown almost 70 miles away and found in Anderson, South Carolina.

A man stands on second floor piles of rubble amidst the ruins of a demolished business. Only a few partial walls and floors were able to withstand the tornado strike. Photo by Lewis Reed

Stunned survivors survey what’s left of their town in this view of the widespread damage in the city streets. Photo by Lewis Reed

The storm that struck with ‘lightning swiftness’ hit the Royal Theatre straight on, also doing major damage to train cars and train tracks running through town. Utility poles were blown over and hung with twisted metal. Photo by Lewis Reed.

This photo documents the power of the tornado to toss around even massive railroad cars. Photo by Lewis Reed

Shambles of homes struck by the tornado. The twister stripped trees of their leaves and left branches hung with twisted metal. Photo by Lewis Reed.

Eight to ten feet of debris piled up along a street while a few houses remain erect despite having sustained damage. Photo by Lewis Reed

Many of the businesses experienced extensive damage. Some stores later offered “tornado sales” to dispose of the damaged goods. Photo by Lewis Reed

House leaning at a precarious tilt after having apparently been moved from its foundation. Photo by Lewis Reed

The death toll in Gainesville was officially 203, though some accounts place it higher. Property damage was in excess of $13 million dollars, or what would be $1.3 billion in damage by today’s standards. More than 1,600 persons were injured and more than 750 homes were damaged or destroyed. The storm that hit Gainesville on April 6, 1936 remains the fifth deadliest tornado in U.S. history. President Franklin Roosevelt toured the city three days later, and returned in 1938 to rededicate the courthouse and city hall after a massive citywide rebuilding effort.

Sources:

Wikipedia – 1936 Tupelo–Gainesville tornado outbreak

The Digital Library of Georgia

Rockville’s First Manual Training School, 1913

One of my favorite things to do is explore details in old photos and to try and figure out what things are and what the picture is. I was immediately intrigued by this photograph when I saw it in one of my grandfather’s albums. The caption on the photo was, “Manual Training Work at R.H.S. 1913”.

What first struck me about the photo is, it appears to be what used to be the inside of an old school classroom. My eye was first drawn to the chalkboard that runs across the front of the room and down the side. When I looked at the details by enlarging it, the writing on the chalkboard reveals a M-F weekday class schedule. I can just barely make out, Algebra and Latin. The rest of the subjects are illegible.

But I was also intrigued by the caption… what exactly is “manual training” in education, anyway? According to google, the Manual Training movement was the precursor to the vocational training programs in our schools today. First used in the United States in the 1870s in the training of engineers, the movement spread rapidly to general public education. The student would learn to skillfully use tools in drafting, mechanics, wood or metal working, and then would be able to transfer this knowledge to almost any kind of tool or setting.

The Rockville Manual Training School opened on January 21, 1901, with over 50 students admitted.

From “The Montgomery County Story” Vol. 24, No. 2, May 1981 by E. Guy Jewell

At a meeting held on January 8, 1901, the Rockville Manual Training School was established by order of the Board of County School Commissioners. On February 21, 1902, Wilson S. Ward became instructor in Manual Training and remained for several years to develop a course noted as outstanding in the State. In 1908, the School Commissioners opened the Business School in the Rockville High School Building. Prof. Neely Graham, a graduate of the Westchester Normal School and of the Wilmington Business College, was appointed principal of this school. One of the large basement rooms was equipped with business desks and typewriters for the business students.

The classes that were introduced in 1902 eventually grew into the Vocational Course in the High School; the other courses were Academic, General, and Commercial.

Located in Rockville, the school now named Richard Montgomery High School is the oldest public high school in Montgomery County. In 1892, the Board of School Commissioners approved an addition to the existing elementary school in Rockville to create a new “Rockville High School,” serving students from grades one to eleven. The first class of twelve seniors graduated in 1897.

The Montgomery County Sentinel

Snowy Day in 1910 at the Old Montgomery County Fairgrounds

As we’re currently experiencing cold, snowy, icy weather, what better time than now to post these snowy pictures of the old Montgomery County Fair. These snowy images of the Fairgrounds were taken by Lewis Reed in 1910.

From 1846-1932, the Montgomery County Fair took place in Rockville with competitions, entertainment, and food that attracted people from Montgomery County and Washington, DC.

Ice Cold History in Montgomery County (1910)

Men harvesting ice with pitchforks and hand saws in Darnestown, Maryland. Photo taken by Lewis Reed in 1910. Note the blocks of ice stacked up along the shoreline. The exact location of the pond is unknown.

Most people wouldn’t consider the months of January and February a season of harvest in Montgomery County. But in our not so distant past, this was harvest time for—ICE. Rivers, lakes and ponds were generally frozen and ice was harvested like a winter crop to keep food cold all summer long.

Before the first successful ice-making machines were built, ice for refrigeration was obtained through a process called “ice harvesting.” Ice cutters used to risk their lives by going out onto frozen ponds with saws, tongs, and pitchforks and methodically cut and dragged blocks of ice which would be stored in hay-packed ice houses. But people did not put ice in drinks as we do now. The possibility of debris having been in the water as it froze – even a bug now and then – discouraged the idea.

Ice houses were dug into the ground to keep the temperature low; double-thick walls were often filled with sawdust for further insulation, and the blocks themselves were packed in sawdust or straw. When you wanted some ice for drinks or to make ice cream, you wouldn’t pull out a whole block; ice picks, chisels, hatchets and shavers were used to get just what you needed.

I’m not exactly sure what the stone structure is in the middle of the pond, but “google” said it could be an outlet structure to keep the water surface in the pond at its optimum level, which usually coincides with the maximum water level designed for the pond. It is connected to a pipe allows water to exit the water body. This pond must have been on a creek or stream and is very likely no longer in existence.

From The Evening Star, Washington, D.C. December 22, 1904

ROCKVILLE AND VICINITY GENERAL NEWS

The cold weather of the past ten days has frozen the ponds and creeks throughout this county to a thickness of six or seven inches, and the ice harvesting is now the order of the day. The quality of the ice is not regarded as first-class, however, and for this reason many persons will defer filling their houses until later in the winter.

Next time you drop a few ice cubes into a glass or take out a frozen piece of meat from the freezer, perhaps give a momentary thought to how much we take for granted the ability to have ice cold drinks, preserved foods that can be stored for months, ice cream, cold frothy beer, and so many perishable food products. Refrigeration is a modern convenience that we just can’t live without and certainly one that I took for granted until I wrote this!

Christmas Trees and Snow Villages from 100 Years Ago

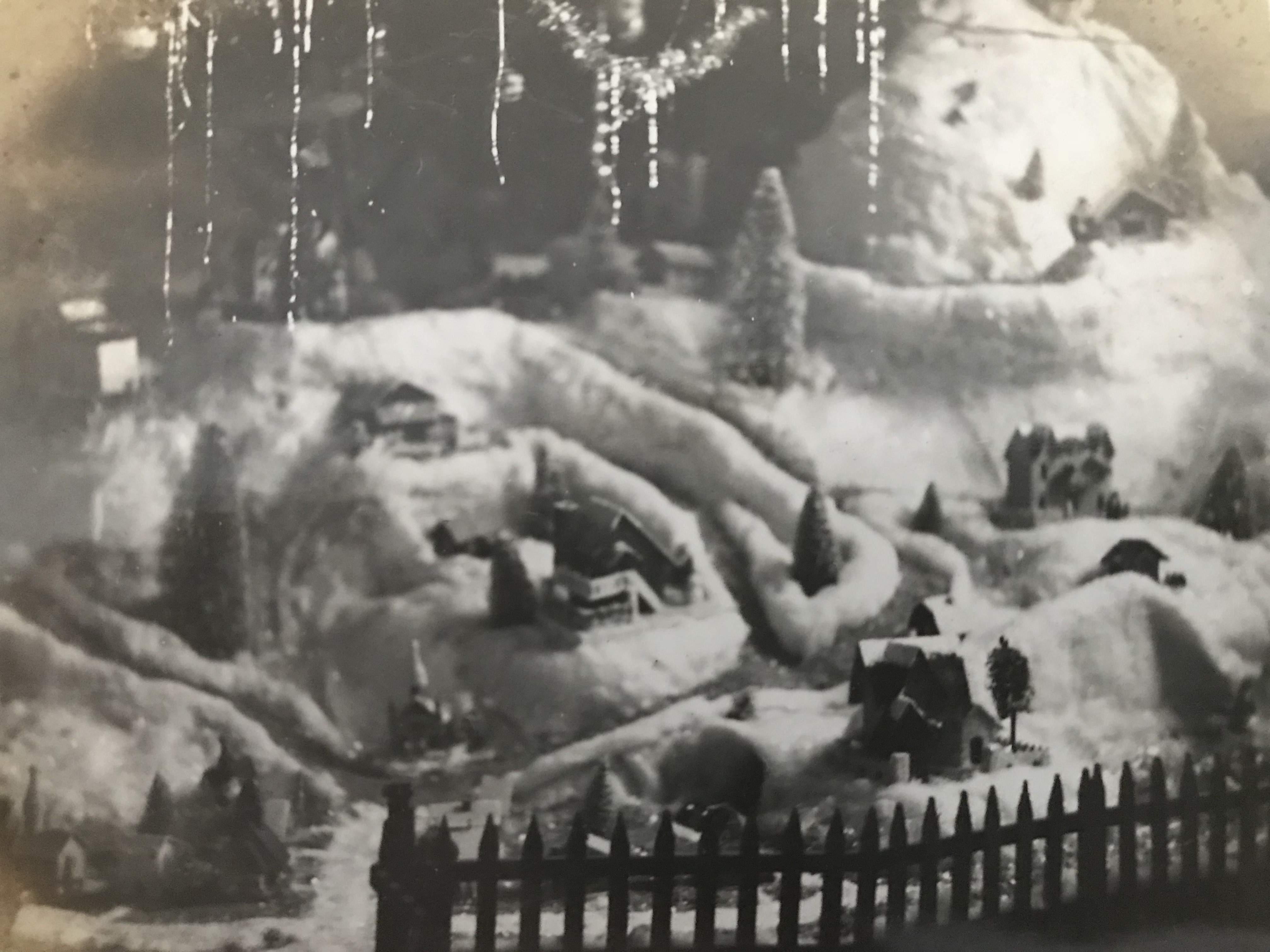

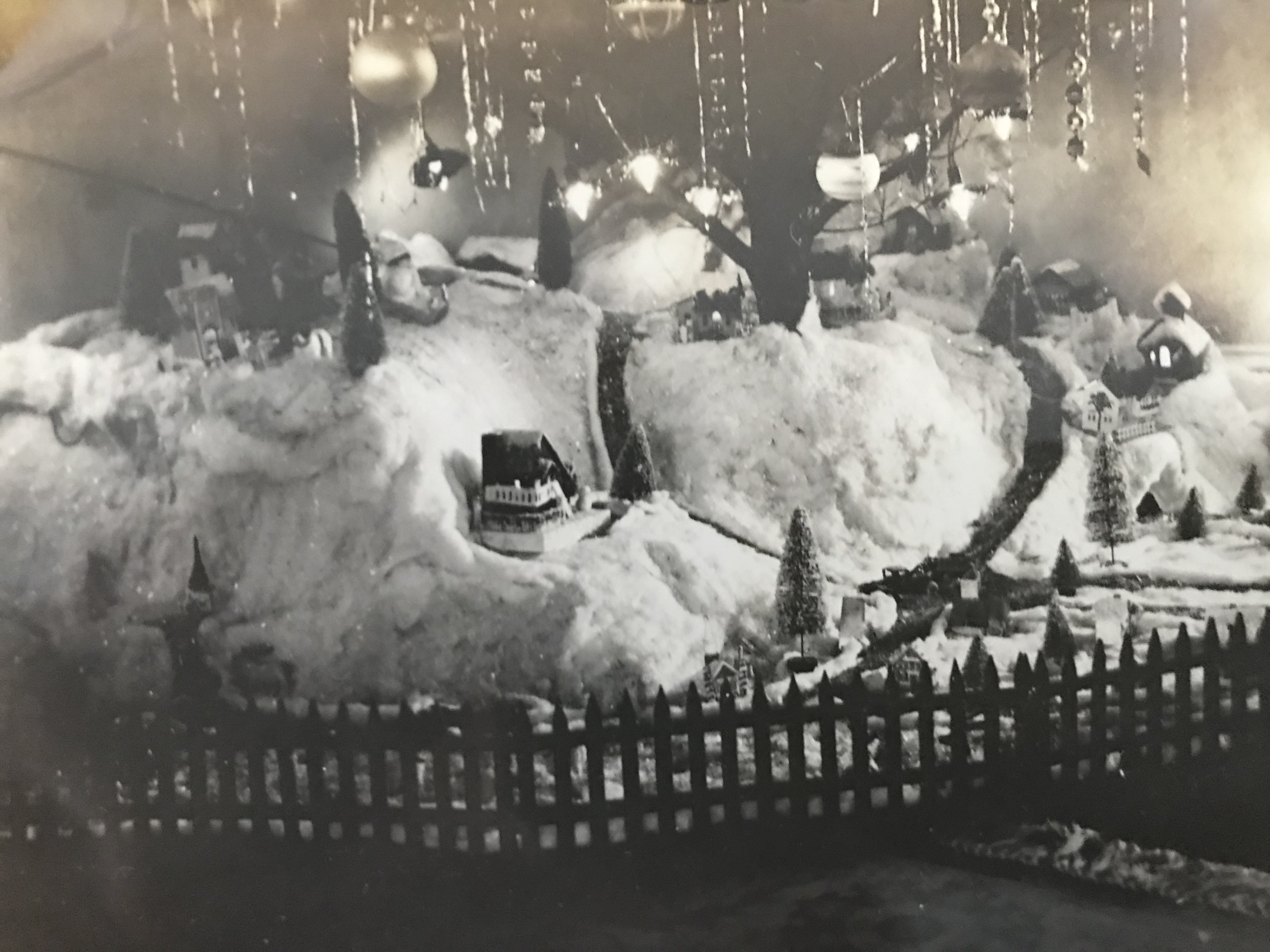

With only a few days left until Christmas, I thought it might be fun to take a look at some photos from Lewis Reed’s collection that show us what Christmas trees used to look like 100 years ago. In those days, there was not wide-spread agreement on exactly what a tree should look like, which made for a lot of creativity. Not surprisingly, they were very different than the perfectly shaped tress we have on display today.

The trees were big back then and always fresh. They went right to the ceiling and were very wide. Early Christmas trees were generally fastened onto a flat board surrounded with fence-rails, snow villages and carpeted with cotton blankets of snow. The tree in the photo below has an abundance of tinsel, which grew in popularity to the point that, by the 1920s, it was common to nearly cover the tree in the decorative material.

So, what is tinsel (aka icicles) exactly? Originally made from strands of silver alloy, tinsel was in fact first used to decorate sculptures. It was only later that it became a Christmas tree decoration, employed to enhance the flickering of the candle flames. In the 1950s, tinsel became so popular that it was often used as a substitute for Christmas lights.

A small snow scene with what appears to be a miniature church is arranged at the foot of the Christmas tree. A popcorn garland adorns the tree. Photo by Lewis Reed

So, where did Washingtonians get their trees?

From The Evening Star, Washington, DC 23 December 1923:

Conduit Road on the long stretch between Glen Echo and Great Falls for many years has been a favorite hunting ground where hundreds and hundreds of families have customarily obtained scrub pine trees for Christmas week. Usually there is plenty of holly and some mistletoe to be found in the rugged and rolling hill lands which are the gateway to Great Falls.

No room for a star on the top of this tree! And just look at those big Santa and Angel dolls. Other fun little details are notable, including a miniature church with picket fence is arranged at the base of the tree. Photo by Lewis Reed

There’s a fine art to decorating Christmas trees that’s been developing since over 100 years ago. People consider lights, garland, ornaments, skirt, and more. But one thing that’s hard to resist sometimes is just filling every available space with decorations. Clearly, that was the case years ago too. What I like about these trees is that they are so randomly shaped and even misshapen. Folks back then didn’t trim them down to a more aesthetically pleasing symmetry like we do today.

The tradition of building miniature Christmas village landscapes, including houses, animals, and other hand-crafted wooden figures, began with the Pennsylvania Dutch in the late 1800s. Mass-produced cardboard houses, sold in dimestores, became popular in the mid-20th century. Today, these villages in good condition can be highly collectible.

Below are photos of Lewis Reed’s snow village set up under the Christmas tree decorated with vintage ornaments, tinsel, and lights. I don’t remember the odd-shaped Christmas trees, but I do remember having a lot of fun helping my grandfather set up the miniature landscapes with the varied figures, little houses, and trees at Christmastime each year. It seemed like a holiday village right out of a storybook.

A rustic picket fence is used to set off the village display. Dangling strands of tinsel hang below the tree. Photo by Lewis Reed

The snow villages were set up in Lewis Reed’s basement on top of a big table beneath a small Christmas tree. He made the snow scenes entirely by hand using wire-covered cardboard and balled up paper to make hills and pathways. The little houses and figurines would fit into the landscape with cotton ‘snow’ all around; and lights would be wired underneath.

Little houses, churches, fences, trees, and pathways were added to the scene. Some of the houses have charming light effects in the windows. The roofs of the houses were decorated with fake snow. Photo by Lewis Reed

These Christmas villages were precursors of the Holiday Villages that were made popular by Department 56 that you see today.

Old-fashioned lights can be seen on the tree, along with lit windows in the houses. The miniature houses usually had holes in the back or the bottom through which tiny lights were placed to provide illumination. Photo by Lewis Reed

Wishing all of you who have stopped in to visit a very Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! Stay safe and enjoy the holiday season with friends and family!

Recent Comments