“The Boardwalk” Along the Waterfront at Chesapeake Beach, Maryland, Early 1900s

In the early 1900s, the Chesapeake Beach Railway Company offered Washingtonians more than transportation, it promised escape. At the rail line’s eastern terminus, a bustling boardwalk emerged along the Chesapeake Bay, carefully designed to attract crowds with hotels, amusements, and sweeping waterfront views. This was a new kind of destination, where leisure was planned, marketed, and delivered by rail.

Lewis Reed recognized the historical significance of this scene and turned his camera toward it. His photographs of the Chesapeake Beach boardwalk capture the rhythms of a day spent seaside: visitors strolling between attractions, pausing to take in the view, or gathering near the latest amusements. Among the highlights of his images is the Griffith Patent Scenic Railway, an early roller coaster whose curves and speed symbolized the era’s fascination with innovation and thrill. (click on thumbnails to view gallery)

Reed’s photographs preserve more than a popular resort, they document a moment when railroads shaped recreation and when leisure itself became part of the modern experience. Through his lens, the Chesapeake Beach boardwalk is frozen in time, offering a vivid glimpse into how Americans relaxed, traveled, and found excitement at the dawn of the 20th century.

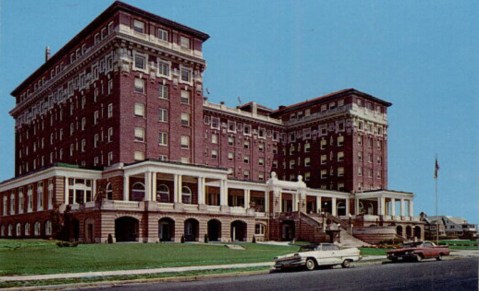

Then and Now: Hotel Cape May, 1919

People have been visiting Cape May, “the nation’s oldest seashore resort,” for longer than America has been a country. That makes Cape May the perfect place to look back on over 100 years ago and from today — then and now.

A bit of Hotel Cape May history: The Christian Admiral, formerly Admiral Hotel and Hotel Cape May, was a luxury beachfront hotel located in Cape May, New Jersey. Opened in 1908, as the Hotel Cape May, the ornate hotel was abandoned five years later due to bankruptcy. It was then sold at a Sheriff’s sale. The hotel was leased by the War Department as a hospital from 1918-1919 during WWI. Afterwards, it was again abandoned. In 1932, the Admiral Hotel company purchased it and renamed it the Admiral Hotel. They too went bankrupt in 1940. The military returned for WWII from 1941 to 1945 and afterwards it was once more sold at Sheriff’s sale. It opened and closed multiple times before being abandoned again in the 1950s. Reverend McIntire saved it from demolition in 1963, and operated it until his organization too, went bankrupt. The Christian Admiral never made a profit for any of its owners and was the cause of six bankruptcies. Nonetheless, it was a gorgeous hotel and one of the most recognizable and beloved buildings in Cape May. The people who liquidated McIntire’s organization shopped the hotel around, but it was deemed too far gone to save. Engineer estimates were $20 million and above, just to make it structurally sound and from $60-$80 million to restore it. The hotel was razed in 1996.

Hotel Cape May (THEN): The Christian Admiral Hotel, originally known as the Hotel Cape May, was erected in the Beaux-Arts style between 1905 and 1908. When opened on April 11, 1908, it was the world’s largest hotel. Completed behind schedule and over budget, Hotel Cape May was part of a development project intended to bring wealthy visitors to the city and rival East Coast resorts such as Newport, Rhode Island. During its existence it would undergo five bankruptcies and ownership changes.

Edgar was a partner with his brother Lewis Reed, in Reed Brothers Dodge. During WWI, Edgar served as a Sergeant in the U.S. Army Medical Corps from February 1918 to August 1919 and had been posted to GENERAL HOSPITAL NO. 11 in CAPE MAY, NEW JERSEY. The spirit of patriotic service which swept the country prompted many persons to offer their properties to the War Department for hospital purposes. These offers included buildings of every conceivable kind, such as department stores, private establishments, hospitals, and properties in large cities. It was found that many of these could be obtained and converted into hospitals much more expeditiously than barrack hospitals could be constructed, and at less cost.

The Surgeon General recommended that the War Department authorize the leasing of the Hotel Cape May for use as a general hospital on December 18, 1917. The Hotel Cape May was located on the Ocean Drive, at the eastern end of the city, and within 100 feet of the beach of the Atlantic Ocean. Opened first as GENERAL HOSPITAL NO. 16, the designation was changed to GENERAL HOSPITAL NO. 11, March 14, 1918. The enlisted personnel were quartered in tents which were located to the rear of the building.

The Christian Admiral Hotel (NOW): In 1991, the hotel was closed by Cape May City officials. The hotel was demolished in 1996 and the site was reused for a development of single family homes. The demolition of the hotel placed the city’s National Historic Landmark status at risk.

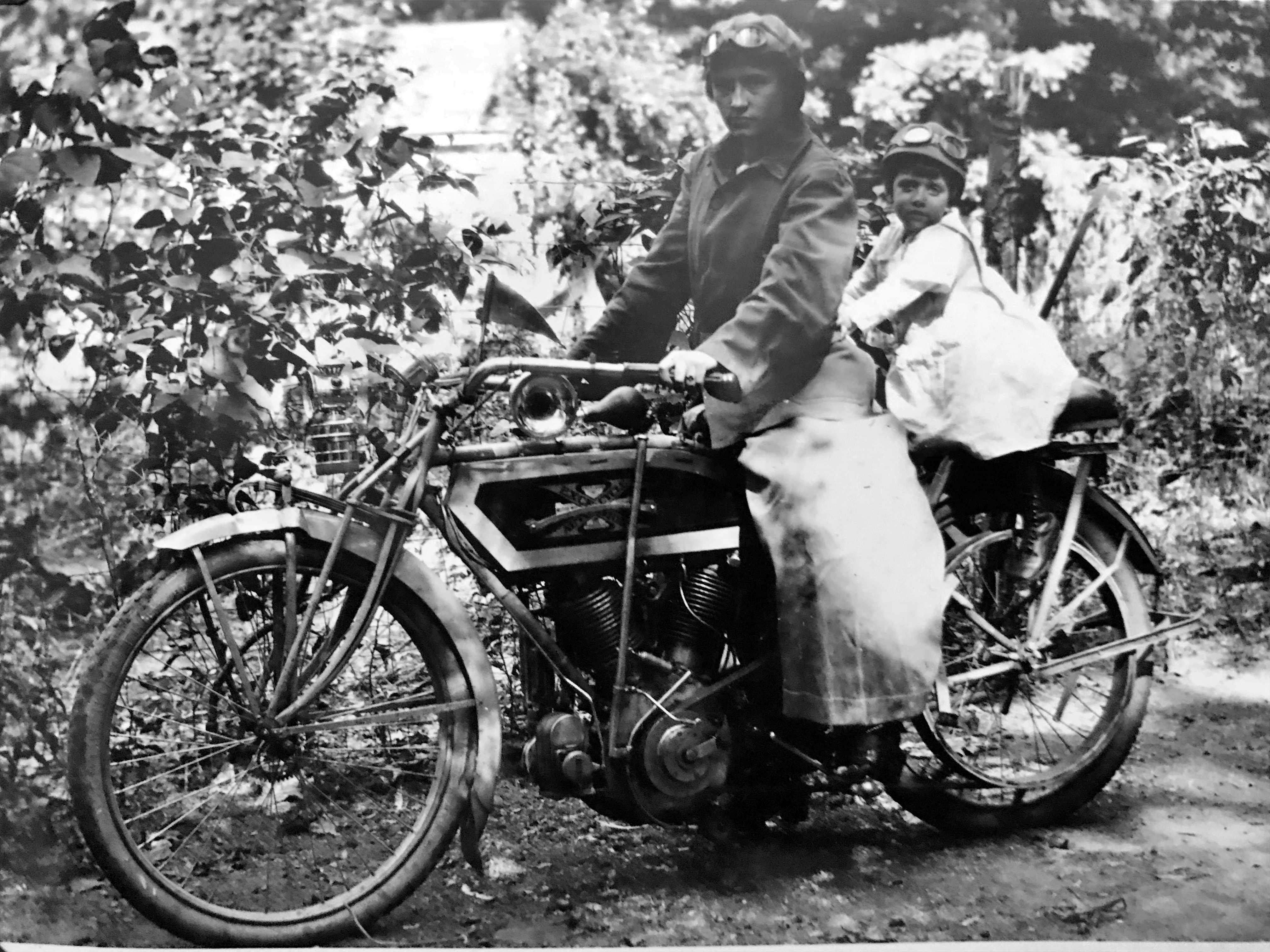

The Reed Sisters and the Spirit of Early Motorcycling

Eleanora Reed with Lewis Reed’s sisters, Geneva and Eva, posing on Excelsior motorcycles. Photo by Lewis Reed, ca. 1912.

At the dawn of the 20th century, motorcycles symbolized the spirit of innovation sweeping the modern age. Adapted from bicycles and powered by the new internal combustion engine, these machines represented freedom, ingenuity, and progress. Before cars dominated the roads, motorcycles often outnumbered automobiles, and it wasn’t uncommon to see riders as young as fourteen traveling the open road.

Photographer Lewis Reed captured this transformative era through his lens, preserving scenes of both relatives and acquaintances astride their machines between the 1900s and early 1920s. His collection offers a rare glimpse into an age when motorcycling was as much a bold adventure as it was a social pastime. Among his most memorable subjects were sisters Eleanora, Geneva, and Eva Reed, who embodied the daring enthusiasm of the time, embracing both the excitement and modernity that early motorcycling so vividly represented.

In the photograph below, a woman and a young child are seated on an Excelsior motorcycle, one of America’s premier machines of the early twentieth century. The child’s cap and goggles, likely intended as playful props rather than functional equipment, evoke the novelty and adventure associated with motorcycling during this era. The woman’s practical riding skirt, tailored jacket, and matching cap and goggles, however, suggest that she was an experienced rider with a genuine familiarity with the motorcycle.

The Excelsior itself showcased early 20th-century innovation, featuring a headlamp for night riding, a handlebar-mounted Klaxon horn with its famous “Ahoo-ga!” sound, and a padded passenger seat for a brave companion. In the early 1900s, many women rode motorcycles before they were even widely allowed to drive cars… while wearing military-style riding gear that shocked more than a few bystanders along the way.

Adding to this story of early American motorcycling is another remarkable photograph below; one featuring a woman and toddler posed on a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. Images like this one remind us how quickly motorcycles captured the public imagination in the years before World War I. They were not only practical for travel over rough roads but also symbols of progress and personal freedom. For women, especially, posing on, or even simply near, a motorcycle was a subtle act of empowerment at a time when societal expectations were still very traditional.

Woman and toddler on Harley Davidson motorcycle, ca. 1912. That slightly timid look says it all; not quite ready to ride, but definitely ready for her close-up! Photo by Lewis Reed.

Preserved through Lewis Reed’s remarkable photography collection, these images remain both a family heirloom and a glimpse into a transformative era. Through his lens, we see not only the evolution of transportation but also the growing independence and confidence of women at the dawn of modern motorcycling.

Braddock Heights, Maryland Then & Now

Looking at old photographs is like opening a window to the past. They invite us to step back in time, sparking both wonder and amazement at how much the world around us has changed. For this post, I’ve paired one of Lewis Reed’s original photographs for the “then” view with a modern Google image for the “now.”

Braddock Heights (THEN): Braddock Heights is a small unincorporated community in Frederick County, Maryland, established around the turn of the 20th century as a popular mountain resort. In its early days, it offered visitors hotels, an amusement park, a skating rink, nature trails, and an observatory from which four states (Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia) could be seen. It even boasted a small ski resort. The Hagerstown and Frederick Railway operated a trolley line connecting Frederick and Braddock Heights from 1896 to 1946. Today, with a population of about 5,000, the area remains known for its sweeping views of Frederick and the Monocacy and Middletown valleys. Braddock Heights takes its name from British General Edward Braddock (1695-1755), who passed through the region during the French and Indian War on April 29, 1755.

Braddock Heights viewed from the Observatory, with Middletown visible in the distance. Photograph by Lewis Reed, circa 1910.

Braddock Heights (NOW): Today, rush-hour traffic flows over the mountain along Alternate U.S. Route 40, stretching from Frederick and I-70 into the Middletown Valley, most of it passing right by the stone pillars at Maryland Avenue that mark the entrance to Braddock Heights.

Local Folklore: Fun Trivia about the Snallygaster

The Snallygaster is a legendary creature rooted in Maryland folklore, particularly in Frederick County and the Middletown Valley. Originating from the German settlers in the 1730s who called it a Schneller Geist meaning “quick spirit,” this fearsome beast is described as a half-bird, half-reptile chimera with razor-sharp teeth and sometimes octopus-like tentacles. The Snallygaster is said to silently swoop down from the sky, preying on livestock and occasionally people, with some early tales even claiming it sucked the blood of its victims.

In the early 1900s, the creature gained widespread notoriety through newspaper reports depicting it with enormous wings, a long pointed bill, steel-hook claws, and a single eye in the middle of its forehead, emitting screeches like a locomotive whistle. The creature was so infamous that the Smithsonian Institution reportedly offered a reward for its hide, and President Theodore Roosevelt considered hunting it himself.

Local farms still bear seven-pointed stars painted on barns, believed to be protective symbols meant to keep the Snallygaster at bay. Beyond scary stories, the legend has evolved into a cultural symbol celebrated today with events like the annual Snallygaster Festival in Frederick County, highlighting the area’s rich folklore heritage.

Though some of its tales have troubling historical contexts, including the use of the legend to instill fear in certain communities during segregation, the Snallygaster remains a memorable and intriguing figure in Maryland’s folklore landscape, blending myth, mystery, and history in one creature.

The Montgomery County Poor Farm: A Glimpse Through Lewis Reed’s Lens

The Montgomery County Maryland Almshouse aka Poor Farm was established in 1789 and torn down in 1959. A modern jail is on its site on Seven Locks Road near Falls Road. Photo taken by Lewis Reed, ca. 1912.

When Lewis Reed raised his camera to capture the Montgomery County Poor Farm around 1912, he was doing more than photographing a building. He was making a choice about what deserved to be remembered.

Reed, known today as the founder of Reed Brothers Dodge, was also an avid photographer with a keen instinct for documenting the everyday life of his community. He photographed barns and bridges, parades and trains, town squares and quiet dirt roads. His lens turned toward the ordinary, and in doing so, he created an extraordinary record of Montgomery County as it was in the early 20th century.

The Poor Farm was not a picturesque subject. It carried with it a history of hardship; established in 1789 as a county-run farm for the poor, the elderly, and the sick, it was a place many preferred not to think about. By Reed’s time, reports described overcrowding, segregation, and unsanitary conditions. Countless residents who died there were buried in unmarked graves nearby. For most, the Almshouse stood as an uncomfortable reminder of poverty in a community that otherwise celebrated progress.

And yet, Lewis Reed photographed it.

Why? Perhaps because he understood, instinctively, that history is not just made up of celebrations and landmarks. It is also written in the places that society tried to hide. His photograph of the Poor Farm framed by leafless trees, a dirt road, and the faint figures of people at its entrance, reminds us that even the least visible institutions were part of the fabric of Montgomery County.

Lewis Reed’s eye was not sentimental, but it was honest. He recorded what was there, not just what was pleasant to see. By turning his lens on the Poor Farm, he acknowledged its existence and its place in the community’s story. Without that decision, we might have no image at all of this building that stood for more than a century and was torn down in 1959.

Today, this photograph is one of the few surviving visual records of the Montgomery County Poor Farm. It endures because Reed believed it mattered. As he might have said himself:

I photographed barns and houses, streets and machines, but also this place because it, too, was part of us. The Poor House was not grand, but it stood for something true about our county. Buildings vanish, memories fade, but a photograph holds them steady. Someday, when the Poor Farm is gone, this image may be all that remains. That is why I pressed the shutter.

Find more photos like this and much more on Montgomery History’s online exhibit, “Montgomery County 1900-1930: Through the Lens of Lewis Reed“.

Recent Comments